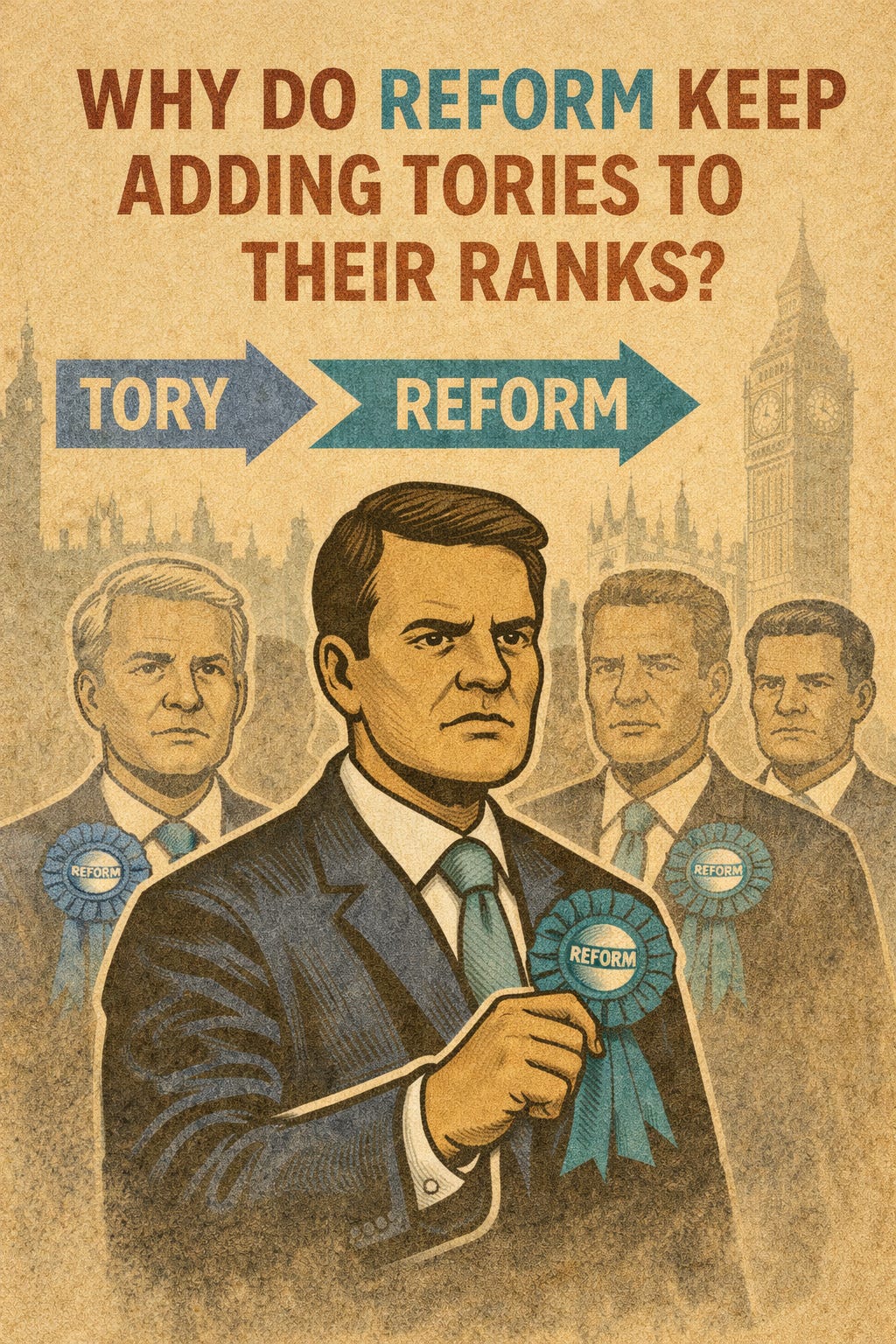

Why Do Reform Keep Adding Tories to Their Ranks?

With Nadhim Zahawi joining the Tories today, it raises the question, why are so many Tories turning to Reform?

Before we get into it, it is worth saying that it’s being reported that Zahawi has defected to Reform because he was not offered a peerage (a lifetime honour granting access to the House of Lords) by the Conservatives. This is in keeping with Nadeem Dorries who also defected to Reform after being refused a peerage — showing the quality of the politicians within the Conservative Party and now Reform.

Back to the title question, Reform and Farage have built their brands on being anti-establishment and offering something politically fresh. So why do they keep on appointing former Tory ministers like Nadhim Zahawi to their ranks?

There is one obvious answer, that both Reform and Farage are not anti-establishment and the projection of that image is entirely inauthentic, but there is another reason for appointing so many Tories.

Farage and the Establishment

Farage went to Dulwich College, one of the most expensive independent schools in the country, where he repeatedly racially abused other students. After leaving school, Farage went to work as a commodities trader in the City of London. This is perhaps unsurprising considering his father Guy Justus Oscar Farage (surely a man of the people) was a stockbroker, suggesting a hint of nepotism.

Farage joined the Conservative Party in 1978 and only left in 1992 because of the Tories willingness to work with the European Union. However, Farage has continued to flirt with the Tories who are his establishment friends. Ultimately, it’s Farage’s love of the establishment and the fact he is friends with many Conservative Party insiders that explains his willingness to bring them on board. He doesn't care about the image it sends to the public, it is the fact that these are the people he likes to spend his time around, he wants to be respected by, and assert power over.

Reform’s embrace of Tories

Reform is now populated by former Tory councillors, MPs, advisers, and activists who have simply changed colours rather than politics. Reform is not about offering new politics, just rebranding the old, worn out establishment politics they are supposed to oppose.

The Conservative Party is in crisis. Years of austerity, corruption scandals, broken promises, and economic mismanagement have left it toxic. Kemi Badenoch is useless and unpopular. But, there are many powerful interests who want a party that stands for the exact things that the Tories have historically supported, just without the baggage. For ambitious politicians and right-wing donors, Reform offers continuity without accountability.

Reform allows ex-Tories to rebrand themselves as rebels and attempt to escape being linked to decades of failure. By ‘swapping’ sides they can sidestep their own role in enabling the national decline. In this sense, Reform is a lifeboat for a sinking political class.

This helps explain why Reform’s leadership, candidates, and councillors so often share the same ideological DNA as the Conservatives they denounce. The language may be angrier, the tone more populist, but the ideology is familiar: low taxes, hostility to regulation, scepticism of redistribution, and a deep reluctance to challenge entrenched wealth and power. That continuity is now visible in local government. They promise to reduce taxes and cut “inefficient” government, yet all councils controlled by Reform have raised taxes, despite their campaign pledges.

The irony is sharp. Reform campaigns nationally on anger at elites, at taxation, at a system “rigged against ordinary people.” Yet in power, the party has shown no appetite for structural reform. Instead, it has adopted the language of change while offering continuity.

Conclusion

Reform’s instinct is managed decline rather than challenge the causes. Just like the Tories. Reform’s transformation into a party of ex-Tories is not accidental but structural. It reflects the limits of right-wing populism in an era of deep wealth inequality and austerity. Without a credible economic alternative, anti-establishment politics quickly becomes establishment politics with a mask on.

For voters, the lesson is a familiar one. A change in party label often does not mean a change in politics. Reform may talk like a revolt against the system, but it’s the same people, the same decisions, and the same costs passed on to those least able to afford them.

The move may backfire, but only time will tell. In the meantime we all need to do our bit to make sure that this information is known. The current mainstream parties might seem disappointing, but Reform are not offering new ideas, and they are not the answer.