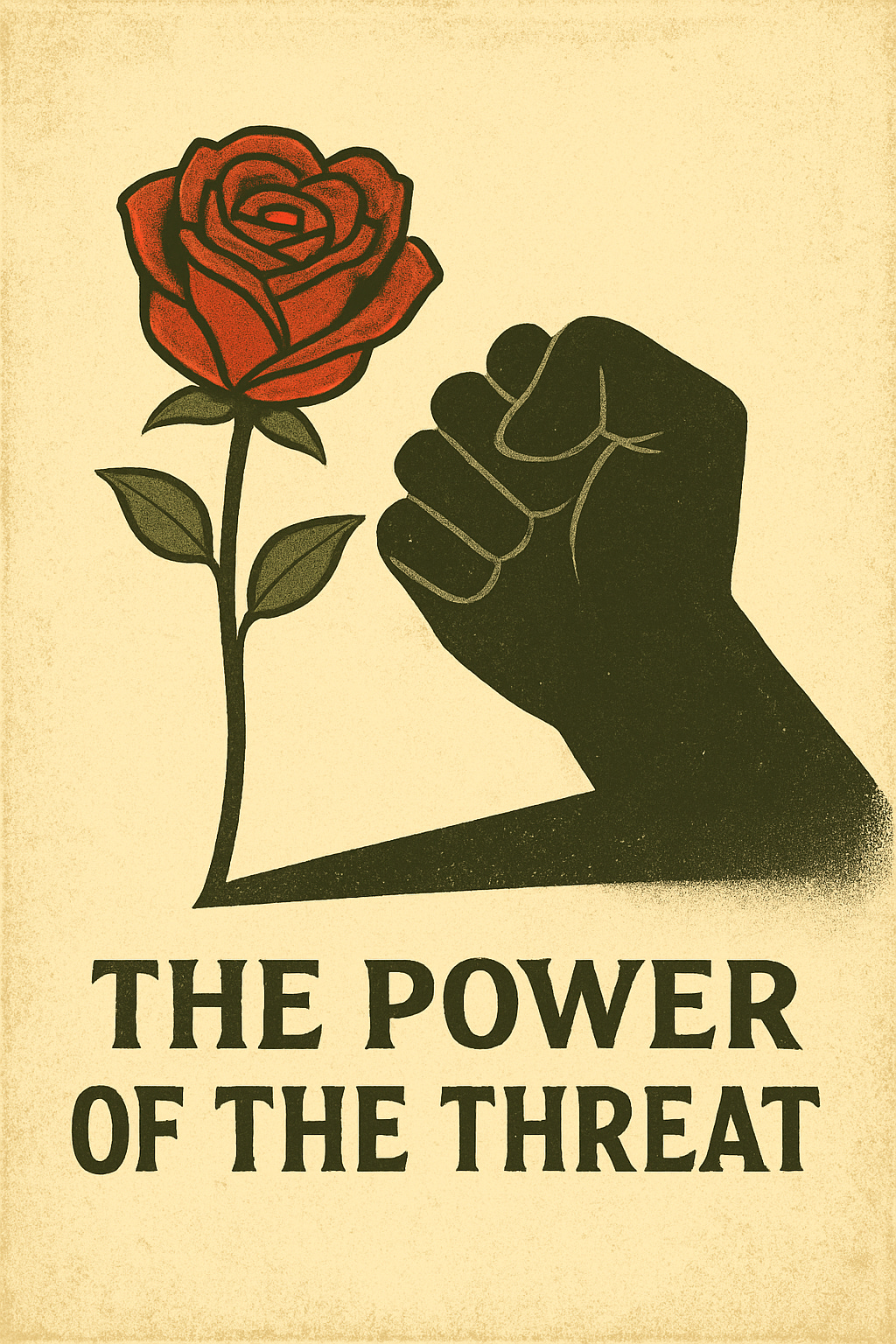

The Power of the Threat: Rethinking Nonviolence for an Unequal World

Dr North provides some comments on his recent publication in the Journal of Pacifism and Nonviolence.

Can a threat ever be peaceful? At first glance, the idea seems absurd. Threats, after all, seem intended to frighten, to coerce, to suggest harm. But my new publication in the Journal of Nonviolence and Pacifism challenges that assumption — arguing that, under certain conditions, threats can be a nonviolent and even peace-promoting tool for the powerless. Titled “Nonviolent Methods of Power Redistribution: A Case for Utilising Threats of Violence” the article interrogates the question as to whether threats must be violent.

My argument is something quietly radical: that threats, when used strategically, can serve nonviolent ends. Rather than being tools of aggression, threats can become instruments of redistribution — a means for the powerless to compel the powerful to the negotiating table without the need for bloodshed and destruction. My article investigates how groups with limited political or economic power — from striking workers to marginalised communities — can use threats strategically to redistribute power and avoid violence.

The Threat as Leverage

The article asks readers to think differently about what it means to “threaten.” In most contexts, threats are associated with aggression — the boss threatening an employee, the bully threatening a victim, the superpower threatening a weaker nation. But in deeply unequal situations, the logic shifts. Sometimes, it is the weaker side that issues a threat — not because they want violence, but because they’re struggling to prevent it.

Drawing on the work of Georges Sorel and the late 19th-century syndicalist movement, the article revisits a time when organised labour wielded the idea of violence, not the act itself, as a form of moral and political leverage. Strikes, boycotts, and the looming spectre of uprising were taken seriously because of the potential destruction they signalled. However, Sorel and the workers did not want bloodshed; they wanted respect and improved conditions, and the credible possibility of disruption forced elites to negotiate.

That same dynamic can be seen today. In Sweden, for example, the industrial union IF Metall has been in a high-profile standoff with Tesla over collective bargaining rights. The union’s threat of strike action, supported by other labour groups, has split the interests of Tesla and the Swedish government, creating pressure for negotiation without violence or chaos.

In this sense, threats functions as a kind of pressure valve — a mechanism that prevents the eruption of real violence by ensuring the powerful cannot simply ignore those beneath them. To threaten, in this view, is to signal capacity, resolve, and agency with a demand for recognition in a system that rarely grants it freely.

Addressing the Tension

But the article does recognise a tension. Frantz Fanon’s critique of nonviolence casts a long shadow over this discussion. Fanon argued that colonised people reclaim their humanity through violence — that the catharsis of struggle is inseparable from liberation. Against this, the idea of a “nonviolent threat” risks sounding naïve or, worse, complicit in maintaining systemic oppression.

This is the paradox at the heart of the article. Can the threat of violence really be nonviolent? The answer is not simple. It depends on intention and effect. If a threat reduces the overall likelihood of future harm, it might paradoxically serve the cause of peace. But if it entrenches fear, domination, or repression, it becomes indistinguishable from the violence it claims to avoid.

A New Ethics of Nonviolence

As the world faces rising inequality, political polarisation, and ecological breakdown, new strategies for nonviolent resistance are urgently needed. Strikes, boycotts, and protests have long been the tools of the powerless. Adding “nonviolent threats” to that repertoire may sound paradoxical — but, as I argue, it might be exactly the kind of paradox that peace requires.

Protest movements from Manchester to Minneapolis have rediscovered the power of disruption, of pressure, of collective threat. The lesson from Sorel and Fanon, and from this new scholarship, is that real change rarely happens through polite appeals. Sometimes, it takes the credible possibility of unrest to make peace possible.

The Northern Reflection

At its core, this article speaks to a broader Northern truth — that dignity and fairness are rarely given freely, but must be asserted, together, through solidarity. The threat, in this light, becomes not a weapon but a warning: that a society ignoring the cries of the powerless risks awakening something far more dangerous.

The challenge is not to abandon nonviolence, but to anchor it in strategy, not sentiment. Because peace, if it is to mean anything, must be built not on silence, but on strength.