The Legacy of Fascism on the Camino de Santiago

Henry North reflects on his 10-week pilgrimage on the Camino, exploring the legacy of Spain’s fascist regime - including a revealing trip to Madrid.

In September 2024 I walked various routes of the Camino de Santiago, a pilgrimage across Spain. From stumbling into bars celebrating communism to visiting a temple of fascism, I saw firsthand the divisive nature of modern Spanish history and politics.

Introduction

As I walked hundreds of kilometres along the Camino de Santiago, travelling at a slow pace allowed me to find traces of Franco’s fascist legacy in everyday places.

The Camino de Santiago is an ancient pilgrimage route that has been walked for over 1,200 years, ending in the cathedral city of Santiago de Compostela. I followed parts of both the Camino del Norte and the Camino Francés - starting in San Sebastian and finishing in Madrid – not for religious reasons, but as a cheap way to backpack through northern Spain. For the money I saved on accommodation and travel, I planned to spend on wine and tapas.

After spending a year learning Spanish, I wanted the chance to practice, but I also quickly became interested in the country’s modern history and its politics. What began as casual reading soon turned into a fascination with the Spanish Civil War. Walking the Camino became more than a backpacking trip to speak some Spanish – it was a chance to see how the scars of the civil war are felt in Spain.

(You’ll also find hyperlinks in the underlined text for anyone interested in further reading.)

A Quick Summary of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish civil war began in 1936 with a military coup led by Francisco Franco against a democratically elected, left-leaning government. Franco achieved victory in 1939, largely due to support from Nazi Germany who used the war as an opportunity to test new military tactics and equipment. After the war, Franco ruled as a ‘Caudillo’ (dictator / strongman) until his death in 1975, enforcing brutal repression of Spanish people who refused to submit along with a complete censorship of the press.

There’s little discussion about the civil war in Spain and beyond due to the ‘pact of forgetting’. A post-Franco political consensus aimed at moving on without addressing the crimes of the past. To some - if optimistic - to bury the trauma of the war and to others, it was a convenient way for those responsible for vicious war crimes to avoid accountability. The war left between 500,000 and 600,000 dead, and with its bitter divisions – often pitting families and neighbours against one another - Spain still has to come to terms with its legacy.

Camino del Norte

The Camino del Norte is a route that starts in Irún and continues through the Basque Country, along the Spanish coast until reaching Ribadeo in Galicia. It then finally heads inland toward its destination, Santiago de Compostela. I walked the whole route.

The Basque Country

So, what does the Camino have to do with the Spanish Civil War? Well, I started my walk on the Camino del Norte in San Sebastián, part of the fiercely proud and politically distinct Basque Country. The region spans northeastern Spain and stretches into southwestern France. It’s a place with a long-standing desire for independence and a culture which feels different to the rest of Spain. The local language Euskara is still widely spoken and is believed to have even predated Latin – it uses x, z and k sounds that are completely different to Mediterranean languages.

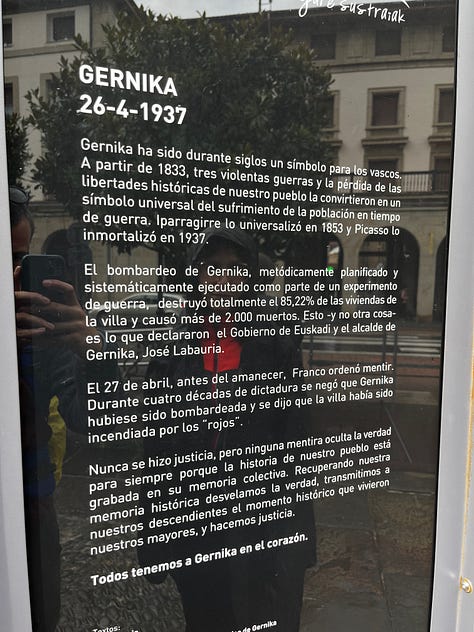

San Sebastian is a beautiful seaside city, but about a four-day walk west brings you to Guernica – the site of one of the most horrendous attacks of the Spanish Civil War. Historically a political and cultural centre for the Basque people, Guernica was also site of a sacred oak, the Tree of Guernica, where leaders swore to uphold the traditional Basque laws. But in 1937, that symbolism was destroyed when German aircraft, on behalf of Franco, carried out the first aerial carpet-bombing of civilians in Europe.

In the town square today, there are information panels dedicated to the bombing. They read that 80% of the town’s buildings were destroyed, but statistics can only paint part of a picture. Imagine walking through a quiet market town and suddenly hearing the roar of approaching engines – no warning, no precedent, just chaos and death falling from the sky. Survivors described the streets littered with indistinguishable animal and human remains. On top of the hill in Guernica, you can find a large mural of Picasso’s painting that captures the horror of the day.

The bombing remains engrained in Basque memory. You’ll see small, tiled tributes of Picasso’s painting above shop entrances in Bilbao. Why? Because - even now – the Spanish government has never issued an explicit apology. During Franco’s rule, the regime even blamed the Republican forces for the bombing of Guernica – a blatant lie that the Basque people had to live with for decades.

The Basque’s lack of trust in the central government is still tangible. The Basque people have their own bank, police force and football team which fields exclusively Basque players. But Basque separatism hasn’t always been expressed peacefully. The ETA (Euskadi Ta Azkatasuna) has carried out bombings and assassinations in search for independence. Although officially disbanded in 2018, sympathy for its cause remains, especially in rural areas.

I saw this firsthand about 30km outside Bilbao, when I walked into a place called Libre (Free), hoping for a cold beer and some food after a long day. The walls were decorated with Cuban flags, copies of front pages of the Basque newspaper Gara and political graffiti in the toilet. To all extensive purposes the place was a bar, it looked like one, sounded like one and served beer like one until I said to the man behind the counter, “I like this bar,” and he replied bluntly but proudly with an air of authority,

“This is not a bar, it is a political organisation.”

I felt like a silly tourist. I left around ten, before my accommodation’s curfew, while the locals settled in for seemed like a late night of chatting and drinking.

Leaving the Basque Country

As a modern and metropolitan city, Bilbao showed little explicit acknowledgement of the Spanish Civil War. As I walked westward and once past the boarder of the Basque Country, I started to sense a shift in the politics. In one town, I saw “Stop Islam” graffitied on the side of a house – a big change from the defiant, leftist sentiment I’d encountered days earlier.

But the more dramatic shift in politics came two days later, in a town called Santoña. On the town’s waterfront, I approached a monument which caught my eye because it had the colours of the Spanish Republic colours - red, yellow and purple thrown across it. As I tried to make sense of the monument, an old man stood nearby asked me where I was from.

I said, “Soy inglés” (I’m English), and randomly he replied by shouting, “what are you doing in my country?” three times in a row.

Switching back to Spanish he added, “that’s what all English people say to foreigners in England”. I thought, no they don’t.

He calmed down once he realised I could speak Spanish and even seemed almost apologetic. He then explained that the monument was to Luis Carrero Blanco, Franco’s right-hand man and chosen successor. Blanco was assassinated by the ETA in 1973 in an epic car bombing in Madrid, which the ETA justified by claiming that Blanco symbolised “pure Francoism” more than anyone else.

I came away from the monument and needed to pause. Just 100km from Guernica – a town flattened by Nazi bombs in support of Franco - stood a state-sanctioned monument to Franco’s top aide. Within the space of an hour’s drive, or a couple of days walk, I’d been exposed to the polarising narratives of Spain’s Civil War – each side glorifying their heroes and vilifying the other. The moral ambiguities were political, but they were also personal. I was left scratching my head.

Continuing West on the coast

While the walk along the coast is beautiful, I saw little public acknowledgement of the Spanish Civil War. In Santander there was some graffiti from Coordinadora Juvenil Socialista calling for people to believe in revolution, but no direct reference to the civil war itself.

Perhaps the biggest surprise was the lack of obvious Civil War monuments in Asturias – a province heavily involved in fighting during the war and home to two major cities, Gijón and Oviedo. Asturias is famous for its cider tradition, where locals pour cider from above their heads, spilling a load of it in the process and then drinking the entire glass in one go (something I learnt the hard way). It’s also historically the centre of Spain’s coal mining industry and known for its strong working-class identity. During the Civil War, it was a key site of resistance to Franco’s forces. Today, while remnants of old cold mines still line the Camino and speak for the region’s industrial past, I didn’t see any acknowledgement of the Civil War’s legacy.

One reason for this could be because Asturias was one of the last republican strongholds in northern Spain but Gijón eventually fell, largely due to fascist air raids. In typical Francoist - and general totalitarian fashion – as part of the aftermath of the Civil War, the people of Asturias were victims of systematic purges of suspected leftists and sympathisers, where at least 3,000 - 5,000 people were murdered. While physical monuments are lacking, the song “Santa Bárbara Bendita” became associated with the Republican struggle in Asturias and still acts as a symbolic memory of the region’s resistance.

El Franco

On the western edge of Asturias, there’s a small region called “El Franco”. Since it borders Galicia - the region Francisco Franco was born - I initially assumed it was named after the dictator. Adding to my suspicions, there’s also a “Rúa do Franco” (Franco Street) in Santiago de Compostela, the end point of the Camino, which all seemed a bit on the nose. After researching both the town and the street were named before the dictator came to power but it just doesn’t sit right with me that one of the main streets leading to the famed cathedral in Santiago de Compostela shares its name with such a ruthless figure.

Camino Francés

The Camino Francés is the most popular Camino route and, as the name suggests, it begins in France and crosses the Pyrenees into Spain, passing through Pamplona and beyond. I finished walking this route in Logroño and two moments from that stretch were particularly memorable.

Sierra del Perdón

The first instance of seeing a legacy of the Civil War was walking in the Sierra del Perdón, where a lookout point along a ridge offers a stunning view of Navarre region. The area gets its name from a mythical pilgrim who, after trading water with the devil in exchange for renouncing God, was ultimately pardoned – a wholesome legend. But nearby, another monument remembers a shocking recent memory, there’s a memorial dedicated to victims of the Civil War.

It's a is tall stone pillar inscribed with “no os olvidamos” (“we do not forget you”), surrounded by smaller stones representing the villages and towns where the dead once lived. The monument is a touching memory for 92 people who were killed by the Francoist regime.

What struck me most though, was the information sign nearby. Its wording had been deliberately defaced. Specific phrases – like “assassinated,” “legitimate government” (referring to the Republic), “killed for fighting for justice and democracy”, “without trail”, “silenced” and “murdered” were scratched out.

Whoever’s feelings must’ve been hurt enough to deface the monument had ironically left the phrase calling Franco’s regime repressive untouched. That must’ve passed the censorship test, no arguments there.

Seeing the memorial defaced was chilling. It was a reminder of the continued, lingering support for Franco. People are still willing to deface a tribute to those killed fighting against an illegal, fascist, military coup.

Viana

The second moment that stood out to me was passing through a town called Viana which sits on the boarder of the Rioja region. My first impression was that it was a sleepy town – but I was quickly made to feel uneasy when I saw a series of swastikas graffitied on the walls.

The first one had a big cross through with “No pasarán” (They shall not pass) written above it.

No Pasarán, although controversial for its links to the Communist Party, was a famous anti-fascist slogan during the Civil War. I was a bit confused, why would someone draw a swastika just to cross it out? A few metres later, it became clearer. I saw another swastika on the side of a building, but this one was untouched.

Viana might have been a quiet stopover town for some pilgrims, but not for me. I was happy to leave.

Madrid & The Valley of the Fallen

Madrid - a magnificent city full of culture and history - played a major part in the civil war. I visited Madrid at the end of my Camino, as I was flying home from there and decided to explore some of the city’s historical spots.

Without doubt, the biggest Civil War monument in Spain lies 45 kilometres northwest of Madrid: The Valley of Cuelgamuros (formally known as the Valley of the Fallen). Located in the Sierra de Guadarrama the site is naturally spectacular but the beauty quickly dissolves when you realise the true nature of the site - a monumental basilica built into the side of the rock, a mass grave and a celebration of fascism.

I visited with a friend, and the first thing we saw of the monument – from the motorway - was the cross. At 150 metres tall and 46 metres wide, it dominates the landscape and, on a clear day, is visible from parts of Madrid. It’s enormous.

The Valley of Cuelgamuros is imposing, and it’s meant to be. The drive up is laced with pinecones, it really is idyllic and when you arrive at the basilica its size is breathtaking. Finished in 1959, the monument feels like something from a bygone empire, you just get that feeling that people can’t make things like this anymore. The reason for its decadence is that much of the labour came from Republican prisoners of war, forced to work in slavery conditions as part of their sentences. More than 33,000 people – Nationalist and Republican – are buried at the site, many of them without knowledge or consent from their families.

The entire monument oozes Francoism and fascism – it’s so strong you can almost smell it. The scale of it is belittling, it makes you feel small and insignificant and takes the warmth out of atmosphere (which is difficult in Spain). The Valley of Cuelgamuros feels mean and nasty, the exterior lights look like they’re straight from a horror film – they wouldn’t look out of place in Mordor or Transylvania - but this isn’t fiction.

You pass through some security scanner and you’re inside and welcomed to hell. It’s dark and the place is on the scale of St. Peter’s Basilica. Everything is designed to look down on you, to humble and disorient. The art portrays dramatic religious imagery that glorifies killing in the name of righteousness and the angels look like killing machines. It’s intimidating and uncomfortable but simultaneously grand and impressive- which is exactly the point. The fascists wanted to inspire fear and awe. It’s rule through hierarchy and terror – a philosophy Franco demonstrated in his brutal treatment of the Basques and Asturians.

To top it off, when I was stood outside the basilica, I overheard a British man talking about the monument with a Bulgarian. Not wanting to judge just by appearances, but both looked like knew their way around the inside of a pub and a pork pie. Thinking about what kind of circumstances bought them at the Valley of Cuelgamuros, was a reminder that while the monument exists, it will be a pilgrimage destination for fascists across the world.

El Pardo Palace

About 13 kilometres to the North of Madrid is El Pardo palace, the former official residence of Franco during his time as Caudillo. Its now open to the public, so I went on a guided tour. It was led by an old, grumbling man who was hard to understand, but I caught a mumble saying, “this was Franco’s favourite tapestry” and “this was his war room”. All delivered with no mention – or critique – of the atrocities committed under Franco’s rule. If anything, the tour felt like a tribute. I think my friend and I were the butt of a joke when the guide muttered something in Spanish, followed by “not many English visit here,” and the rest of the tour laughed. I didn’t catch the punchline, but I do know that Franco and his regime weren’t laughing at the British when their tourists started visiting Spanish beaches, inadvertently propping up his economy in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Inside, the palace is a masterclass in mismatched taste. The downstairs is painted a kind of sandy sick colour, while upstairs sports a tired, murky green. Most of the artwork consists of oversized tapestries depicting life in feudal villages – exactly the kind of imagery that fed Franco’s backward, ultra-conservative fantasy of what Spain should be. The whole place shows a delusion, clinging onto a romanticised past that never really existed. The tour, which dragged on for over an hour, felt like a light homage to a dictator who ruled by fear and I was more than ready to leave by the end.

Picasso’s Guernica

Located in the Museo Reina Sofia - after a 42 year stay in the Museum of Modern Art in New York to keep it out of Franco’s hands – Picasso’s Guernica measures 3.5 metres high by 7.76 metres long. Completed in 1937 while Picasso was living in Paris, it was an immediate response to the bombing.

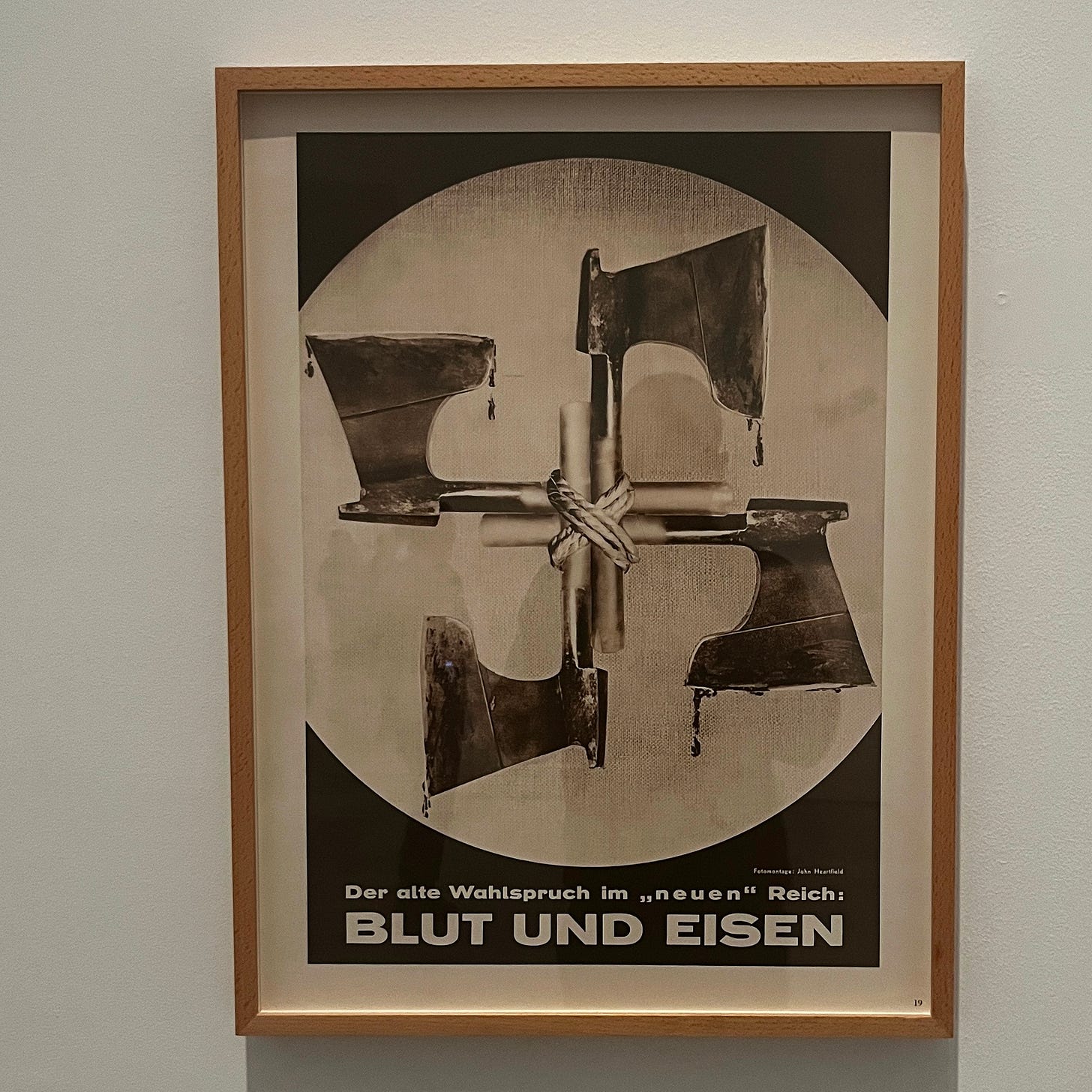

The walk into the exhibition sets the tone. I passed through a series of wartime propaganda - colourful, defiant posters from leftist groups and chilling fascist imagery. One Nazi piece titled “Blut und Eisen” (“Blood and Iron”), features axe heads dripping with blood arranged in the shape of a swastika. It’s the sort of thing which makes you question what kind of person sees that and feels inspired to join the fascists.

The way the exhibition is set up, you can catch an early glimpse of the painting through an arched doorway and then you’re in front of it and it feels like being screamed at.

The sheer scale of Guernica makes it feel almost immersive. At first glance it’s just a chaotic scene. But the longer you look, the more you see hidden details. Even in black and white, different shades creates a layer of depth that drew me in. Hidden behind the initial destruction is further layers of mixes between animals and humans giving the impression of what victims may have seen or been when the bombs fell. Everything reduced to an indistinguishable wreckage.

Another interesting detail - carved finely into the painting - is what looks like an American flag. Perhaps a nod by Picasso to suggest American complicity in the massacre. Companies like Texaco and Ford did business with Franco despite the American’s claiming neutrality. Texaco fuelled the fascists with oil on credit and Ford provided trucks that were used in the war effort.

Guernica is one of the most visceral anti-war monuments ever created, and perhaps the most powerful I’ve seen outside of Ypres. The atmosphere in the exhibition room is one that forces a level of introspection even when your view is blocked by Americans taking selfies.

Montaña Barracks

Now demolished, the Montaña Barracks in the centre of Madrid was the site of one of the earliest and most symbolic clashes of the Spanish Civil War. In July 1936, rebel military officers attempted to seize control of the barracks but were eventually defeated. The failure didn’t stop the broader coup, but it did mark the vicious start. Today, all that remains of the barracks is a sculpture of a horizontal solider which looks a little like a gun, surrounded on three sides by sandbags. There is no plaque explaining the statue, no information on which side the solider belonged and no interpretation of what the monument represents. It felt deliberately noncommittal, as if it wants to acknowledge the violence without the responsibility to explain it. As the last Civil War site I visited in Spain, it was - for me - characteristic of the country’s approach to the conflict’s memory: silent, ambiguous and easy to miss.

Conclusion

I walked a total of 1,075km through northern Spain, passing through regions that felt like entirely different countries – making it hard to sum up my time there. Even in Madrid, contradictions were everywhere. In the Lavapiés district, I wondered into a bar-restaurant and was offered an €8 curry and drink, subsidised by the Unificación Comunista de España, which went down a treat on a backpacker’s budget. But always at the back of my mind as that just 45 kilometres away was Valley of Cuelgamuros, celebrating Spain’s fascist past.

Spain is country of tensions and contrasts. Politics seem to move fast, yet shops rarely open on time and siestas begin and end whenever they feel like it. Maybe that’s the point – Spain refuses to be defined. It’s messy, compelling and endlessly fascinating. And I love it.