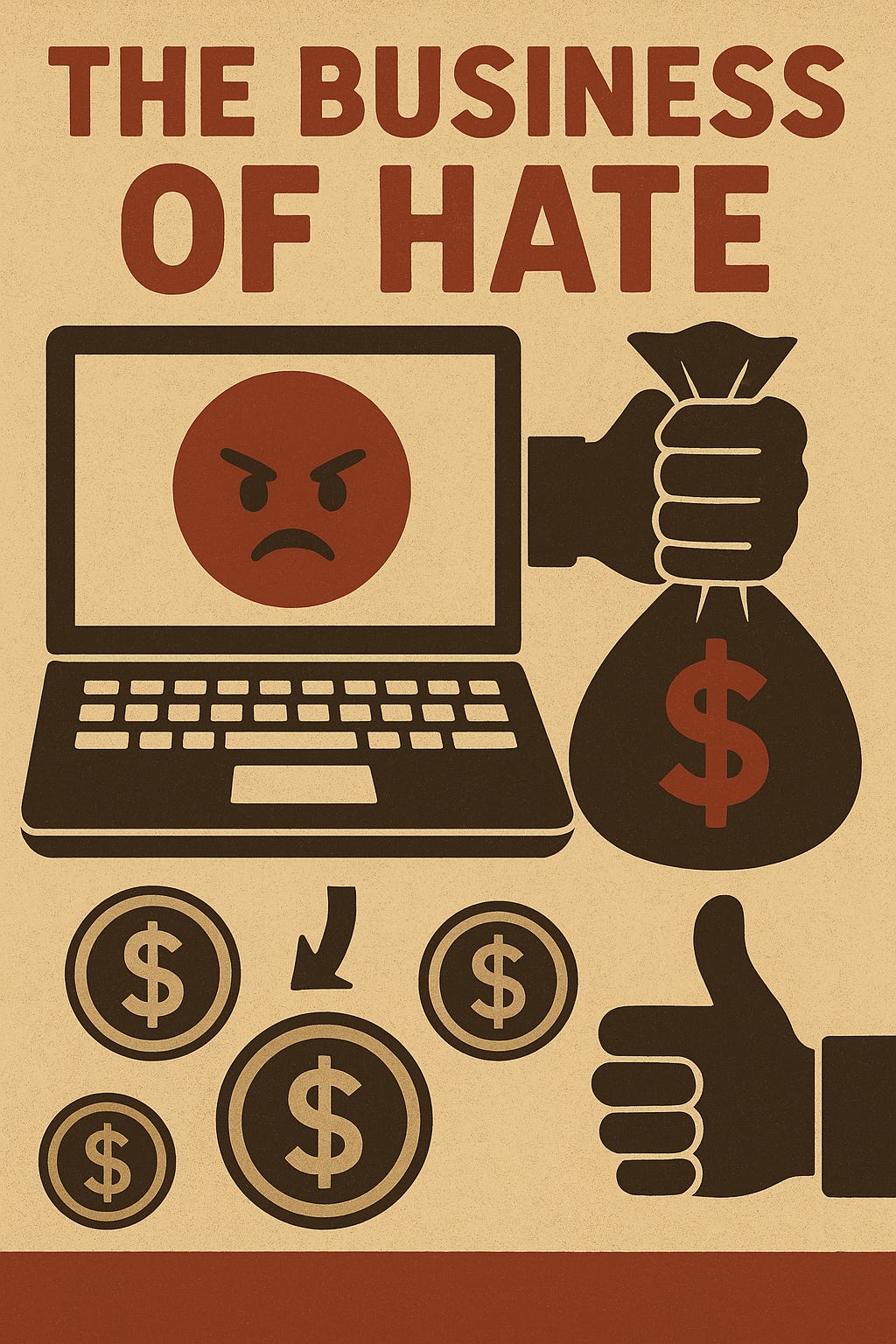

The Business of Hate: Who Profits When We’re Divided?

Dr North's follow up on The Northern Rose's recent podcast on the monetisation of hate.

In our recent podcast, we unpacked how hate is not just an emotion but an economy. Online, outrage has become currency, clicks have become capital, and platforms have learned that division is more profitable than unity. But the story doesn’t end with algorithms. The monetisation of hate reaches deeper into our politics, our media, and our everyday lives.

Hate as a Business Model

Social media platforms thrive on engagement, and nothing engages like anger. Studies show that false or inflammatory content spreads faster than facts, not because people are more gullible, but because conflict grabs attention. Every share, every furious comment, every doomscroll fuels advertising revenue. Hate becomes not an accident of the system, but its engine.

The Outrage Industry

Beyond the platforms, a whole ecosystem of actors cash in. From YouTubers creating controversy to political pundits (like GB News or Piers Morgan) who churn out culture-war talking points, hate pays the bills. The far-right in particular has mastered this model: generating rage, harvesting followers, and then monetising them through donations, merchandise, and memberships. Hatred is repackaged into endless content.

Politics in the Marketplace

The danger is not just cultural but political. When politicians realise that polarisation delivers attention, they lean into it, and it works. The BBC has come under recent pressure because of the disproportionate airtime they give to Reform politicians who thrive on division and hate.

The more bitter the fight, the more airtime they get. Policies are reduced to clickbait. Nuance disappears. Citizens become customers, sold on simplified enemies rather than complex solutions.

The Cost to Society

This economy of hate leaves us all poorer. It deepens divisions between neighbours, spreads mistrust in institutions, and leaves no room for compromise. Most dangerously, it creates an incentive structure where bad faith actors want us angrier, more suspicious, more hostile—because that’s when we’re most profitable.

Those in power recognise that splitting us is what prevents social change. Look at Elon Musk calling for violence on our streets. He doesn’t care about British workers, merely look at the various industrial disputes his companies have been involved in.

It is important to remember the famous phrase offered to us from Aesop’s fable:

United we stand, divided we fall.

Breaking the Cycle

There are ways forward. Regulation of big tech must take seriously the role algorithms play in amplifying hate. Media literacy—teaching people how to recognise manipulation online—should be a public priority. And movements that resist hate need to learn to be just as strategic: building networks, telling compelling stories, and creating spaces where solidarity is more powerful than division.

Shows like Adolescence have addressed the role that parents have to play in combatting the dangerous threat social cohesion.

Conclusion: Starving the Beast

Hate only thrives when it is fed. As long as anger means money, the cycle will continue. The challenge for our time is not just to resist hateful ideas, but to dismantle the business model that keeps them alive. If we can starve the beast, perhaps we can build a digital public square that values truth over rage, and connection over clicks.