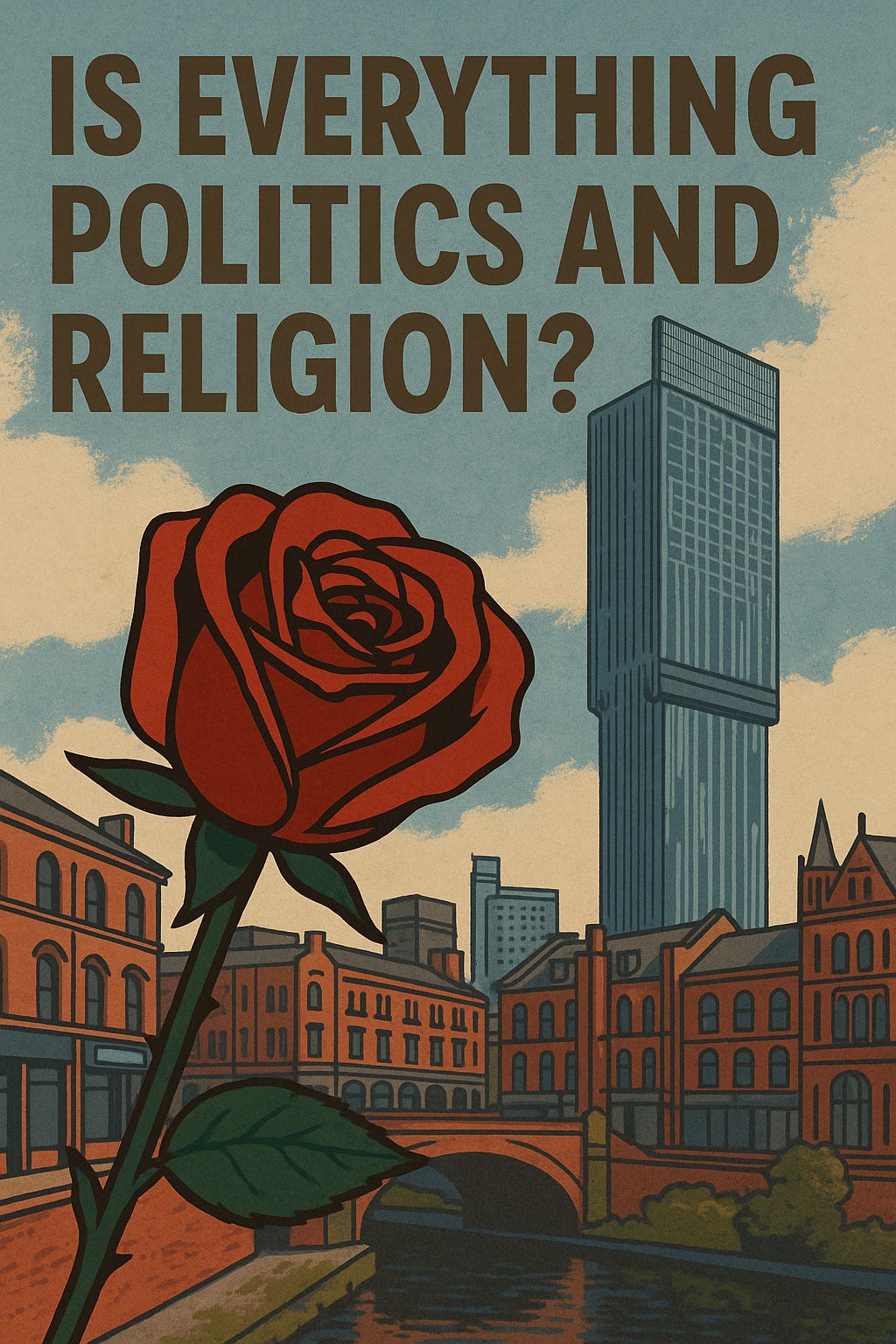

Is Everything Politics and Religion?

Dr Adam North asks whether the everyday choices we make—from what we wear to how we work—are more political and spiritual than we realise.

We often hear the phrase “I don’t talk about politics or religion.” It’s said at dinner tables, at the pub with friends, and in the workplace — often with the hope of avoiding conflict.

But what if the very act of avoiding those subjects is, itself, political? What if politics and religion aren’t just topics we occasionally address — but the lenses through which nearly everything we do, believe, and experience is shaped?

What if everything is politics and religion—whether we admit it or not?

This isn’t just an abstract claim. It's a provocation to look again at the everyday — at housing, food, language, work, family, identity — and ask: What systems of power are at play? What beliefs are being enacted?

Let’s take a closer look.

Politics Isn’t Just Parliament

Politics isn’t limited to elections or party manifestos. At its heart, politics is about power: who has it, who doesn’t, how it’s distributed, and how it’s resisted. Politics is present in how a city is built, who can afford to live in it, who gets the most desirable jobs, what histories are remembered, and what languages are spoken.

When a library or a park closes, when a CEO earns 300 times more than a care worker, when homelessness increases, when someone is stopped and searched because of their race — that’s politics.

And when we say, “I don’t care about politics,” we’re often in a privileged enough position to ignore its consequences, or buffered by systems that protect us from seeing them.

Religion Isn’t Just Church on Sunday

Religion, too, is more than organised faith. It’s about how we make meaning. It’s about ritual, story, purpose, transcendence, morality, and community. Even in secular societies, religion shows up in how we talk about justice, sacrifice, truth, meaning, and redemption.

Political ideologies can become religious in form — nationalism, capitalism, environmentalism, even science when it becomes dogmatic. We attach our faith to these systems and acquire our meaning from them. We construct myths about markets or nations or identities that tell us who we are and what we should value.

We believe in things. And we live by them. Whether we name them as “religion” or not, they are powerful.

The Personal Is Political — and Spiritual

Take something seemingly small: the clothes you wear. They're political — shaped by labour laws, gender norms, and global supply chains. But they can also be religious —worn to express identity, ideological loyalty, modesty, solidarity, or transformation.

Or think of food. What you eat is political: governed by subsidies, scarcity, and culture. It’s also religious: rich with meaning, taboo, ritual, and comfort.

Even silence can be a political statement, a religious discipline, or a spiritual encounter.

The boundaries blur. What we consider “private” choices often rest on deeply political or spiritual frameworks — about what a good life is, what’s fair, who matters, and what purpose are we here for.

Why This Matters

If everything is politics and religion, then nothing is neutral. That doesn’t mean everything is partisan or sectarian — far from it. But it does mean that values are always at work. Every school curriculum, housing policy, algorithm, or advertisement is advancing some vision of the world — some idea of what’s right, normal, or desirable.

Recognising this doesn’t make life heavier. It makes it more alive. It invites us to pay attention. To ask better questions. To understand that even the most ordinary decisions — how we greet someone, where we shop, what we do with our time — are shaped by wider forces and deeper beliefs.

It means that we aren’t just passive observers, we can choose to live more deliberately.

Conclusion: Living in the Tension

Not every conversation needs to become a debate about ideology. But perhaps the line between politics and religion and “everything else” isn’t as clear as we like to think.

When we say we “don’t do politics or religion,” what we may really be saying is: I don’t want to confront the systems and beliefs that shape my life. By not engaging with politics or religion, we are taking a passive role and allowing ourselves to be shaped by the forces around us. And those systems and beliefs aren’t waiting politely in the background. They’re in our homes, our cities, our phones, and our dreams.

So yes — maybe everything is politics and religion. And maybe that’s not a problem. Maybe that’s an invitation.