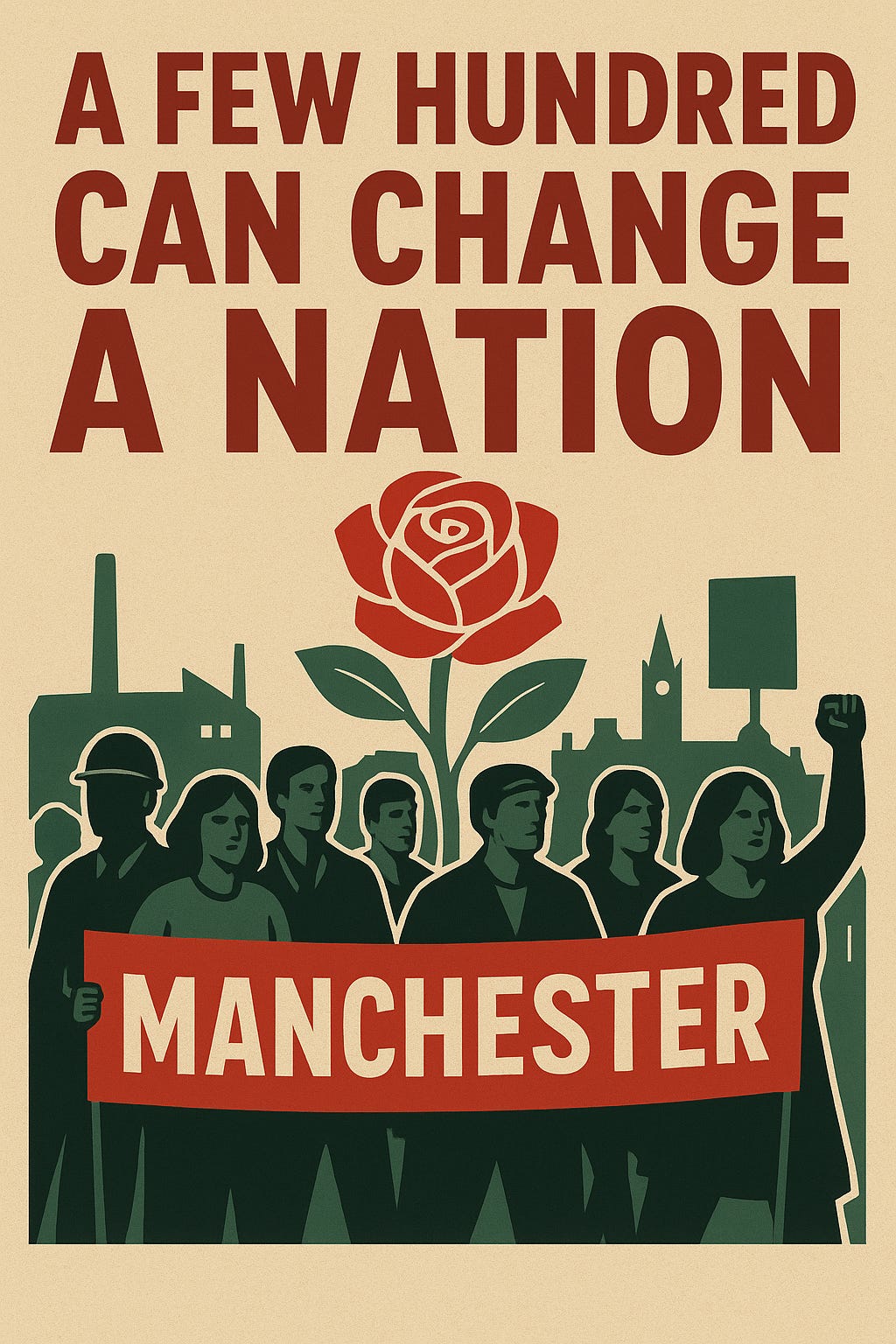

How Many People Does it Take to Change the World?

Dr Adam North discusses how small group of people can change the world

It’s easy to be disaffected by modern politics. To believe that real change isn’t possible and that all politicians are the same. Years of austerity, decreasing living standards, and crumbling public services create the perception that positive change is impossible. However, throughout history, small collections of people have been able to have hugely outsized impact on the direction of nations and international cooperation.

Credit is often disproportionately placed on the leaders of movements, but it is never one person who changes the world and always a collective — which can be relatively small. From the Suffragettes to the ANC, the cumulative effort of passionate individuals gathered for a shared purpose can shift collective perspectives, garner momentum and hope, and drive people to action.

For me, the clearest current example of this phenomenon at play is Gary Stevenson and his influential channel Garys Economics. It would be easy to give Gary all the credit for popularising the policy position of a wealth tax, which is now supported by a majority of Brits, but he is not solely responsible for this upsurge. Gary has successfully built, and been joined by a coalition of actors, who have helped repeat and transmit his message.

Additionally, the new mayor of New York City, Zohran Mamdani, started his campaign with a projected 1% of the vote share, only to win with 50% a year later. Despite running against billionaire funded Andrew Cuomo and threats from ridiculous right-wing commentators that he would destroy New York, Mamdani’s grassroots campaign was able to build momentum and eventually win power promising socialist changes.

Popular support for a wealth tax and the success of Mamdani should provide hopeful examples of how a small group can generate an incredibly loud noise and build a wave of momentum. This concept is often described or referred to as the Overton Window — which suggests that public position shifts overtime as political ideas move in and out of fashion. However, what moves the Overton Window? There is undoubtably a high degree of chaos that influences public perception, but within that chaos, highly passionate, well organised groups can play a pivotal role.

So, if it doesn’t take that many people to change the world, perhaps you could be part of changing it. If your job doesn’t fulfil you, then you are not alone. Rutger Bregman has become a figurehead of the Moral Ambition movement. Instead of chasing money and often becoming cynical, Bregman encourages the most intelligent people to pursue morally meaningful and societally changing work that would better all our lives. This is not a trivial point, especially when as many as 25% of people think their jobs are socially meaningless, but the number is likely much higher.

Bregman offers a very simple test for working out the social impact of your job: “go on strike and see what happens”. If no-one notices, then your job is bullshit. Bregman writes of bankers: “The only strike of bankers that I know of happened in Ireland, 1970. Lasted for 6 months. Economy just kept growing, people didn’t really notice.”

When in conversation with The Guardian, the interviewer asked Bregman, what if changing the world isn’t your passion, Bregman replied “You’ll become passionate about it very quickly.” He’s not wrong. When a fight is truly meaningful, say the battle against big tobacco — which created the deadliest consumer product in world history — it’s hard not to become passionate about work ahead.

Change won’t be handed down from Westminster — not even by those with good intentions. If we want a different future, we’ll have to demand it. And it doesn’t take millions. If just a hundred of us chose to act together, with purpose and a shared goal, we could shift the dial. We could help build a better world.